By Gunhild Borggreen

In the Danish Royal Family’s collections there is a fine old folding screen which today belongs to the Royal Couple. The screen’s paintings and calligraphed poems date from around 1700, and probably came into the possession of the Royal Family in the second half of the 19th century. It was found in a storeroom in connection with the preparations for the special exhibition Japan in the Royal Danish House, together with other objects from the home of Christian IX and Queen Louise. The screen was probably a gift to the couple from family members who had visited Japan.

In this article art historian Gunhild Borggreen, Associate Professor at the University of Copenhagen, sheds light on the screen, which can be seen by the public for the first time in the special exhibition, until 3 September 2017.

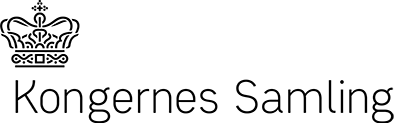

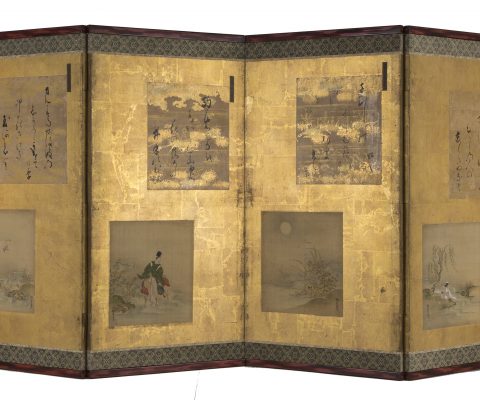

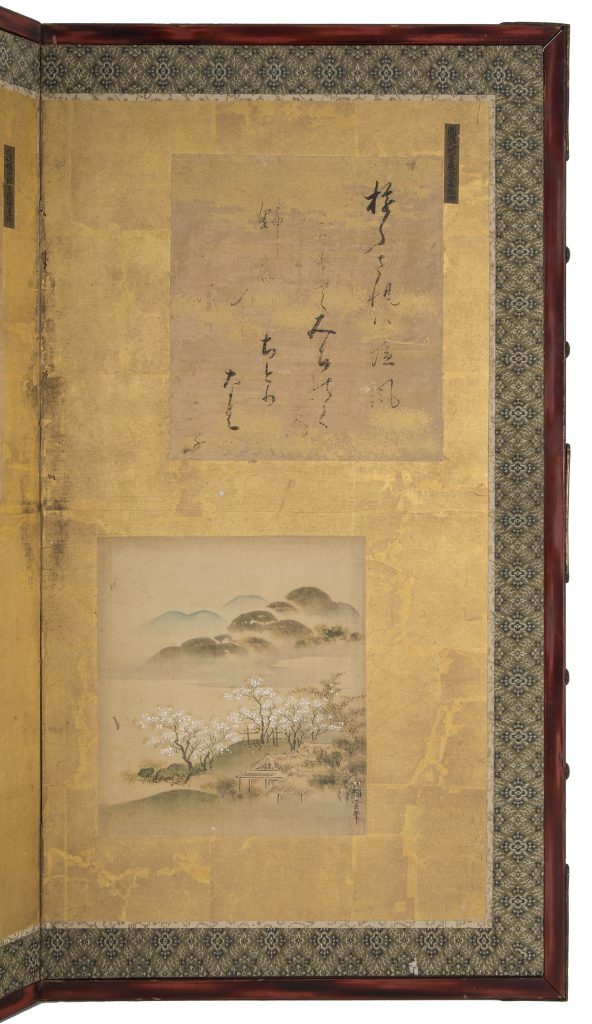

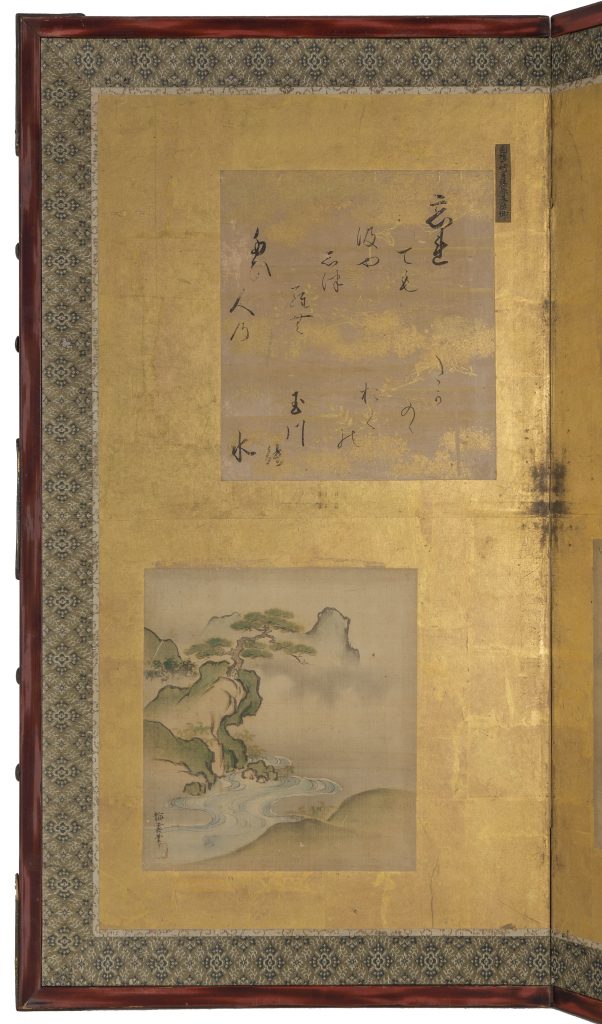

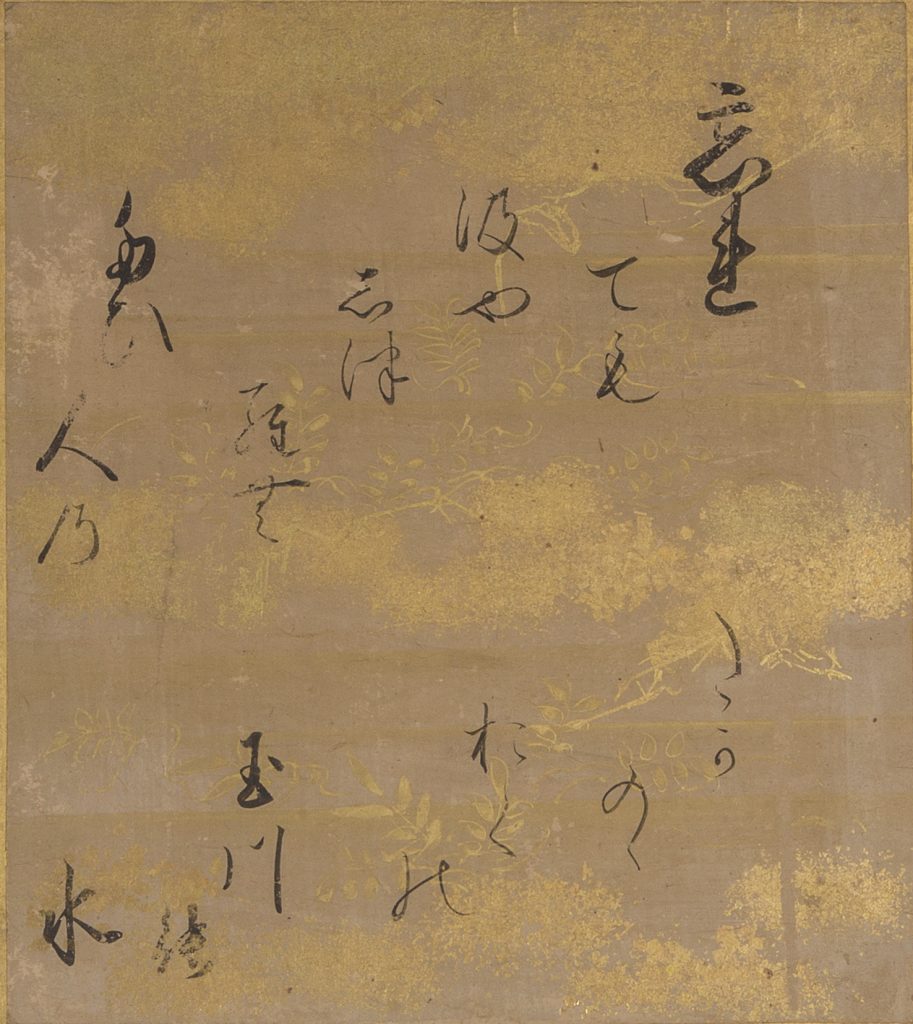

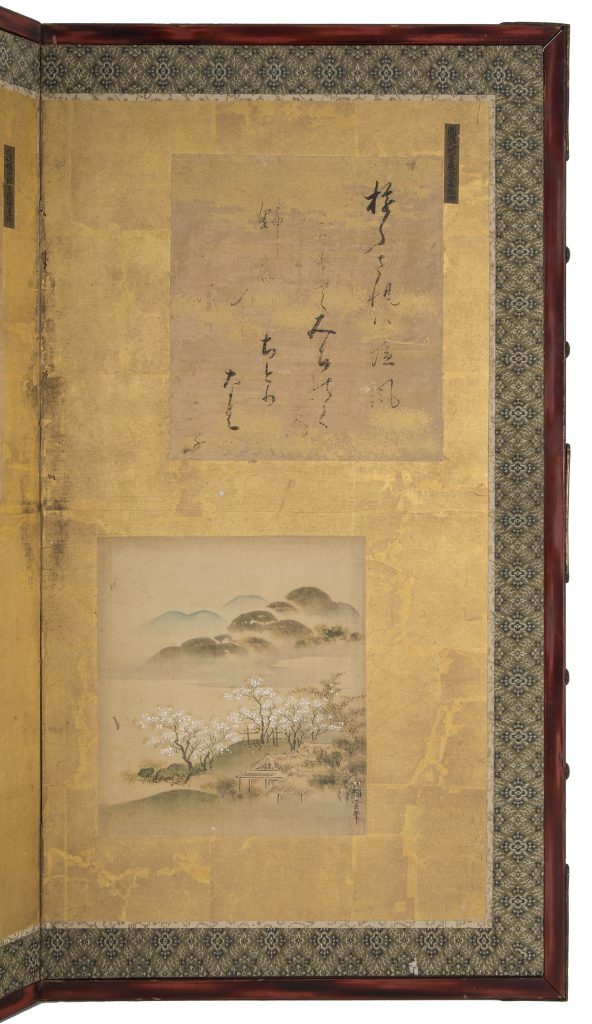

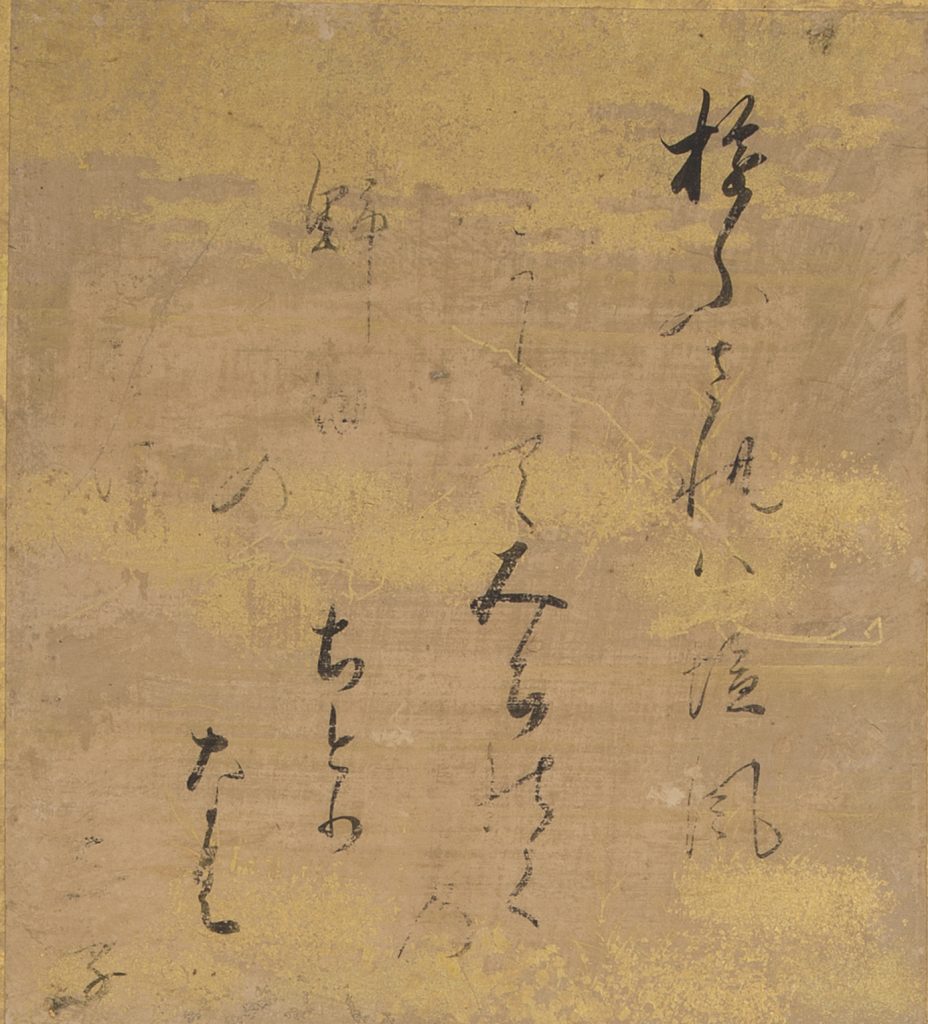

The Japanese folding screen in the Royal Family’s collection is a ko-byōbu, small folding screen, with six vertical panels. Each panel is 64.3 cm high and 34.7 cm wide, and the panels are attached to one another with hinges of Japanese paper, washi, so that the screen can be folded for storage. For display the screen is positioned in zigzag, so that it can stand alone on the floor. The panels are covered in gold leaf, and mounted on each of the six panels is a sheet of paper with calligraphy measuring approx. 20 x 17.7 cm, with a smaller vertical inscription space bearing names measuring 1 x 5 cm a little to the right. A painting on a piece of silk measuring approx. 19.5 x 17.7 cm is placed beneath the sheet bearing calligraphy, offset a little to the left. When the screen is read in the conventional reading direction from right to left, you first encounter the calligrapher’s name, then read the poem, then let the eye move down to the painting, before moving on to the next panel. The sheets of paper bearing calligraphy and the paintings on the Royal Family’s folding screen presumably stem from an album that was made between 1704 and 1715.

The motif on the Royal Family’s folding screen is Mu Tamagawa, The Six Jewel Rivers, and it is a byōbu uta, screen with poems, combined with meisho-e, pictures of famous places. Tamagawa means ‘jewel river’ and refers to the clean, crystal clear water in the rivers. There are six different rivers, each in a different province of Japan, with the name Tamagawa. In the mid-17th century it became popular to collect and reproduce six classical poems which each described a ‘jewel river’. The Tamagawa poems stem from various classical anthologies or collections of poems, and they are all written in the waka form. Waka poems consist of 31 syllables arranged in five lines with a fixed number of syllables: 5-7-5-7-7. The calligraphy for the six poems on the Royal Family’s screen was done by two different calligraphers, Fujiwara Motokatsu and Minamoto Sukemichi. The six paintings were executed by the artist Kanō Baiun (1657-1715).

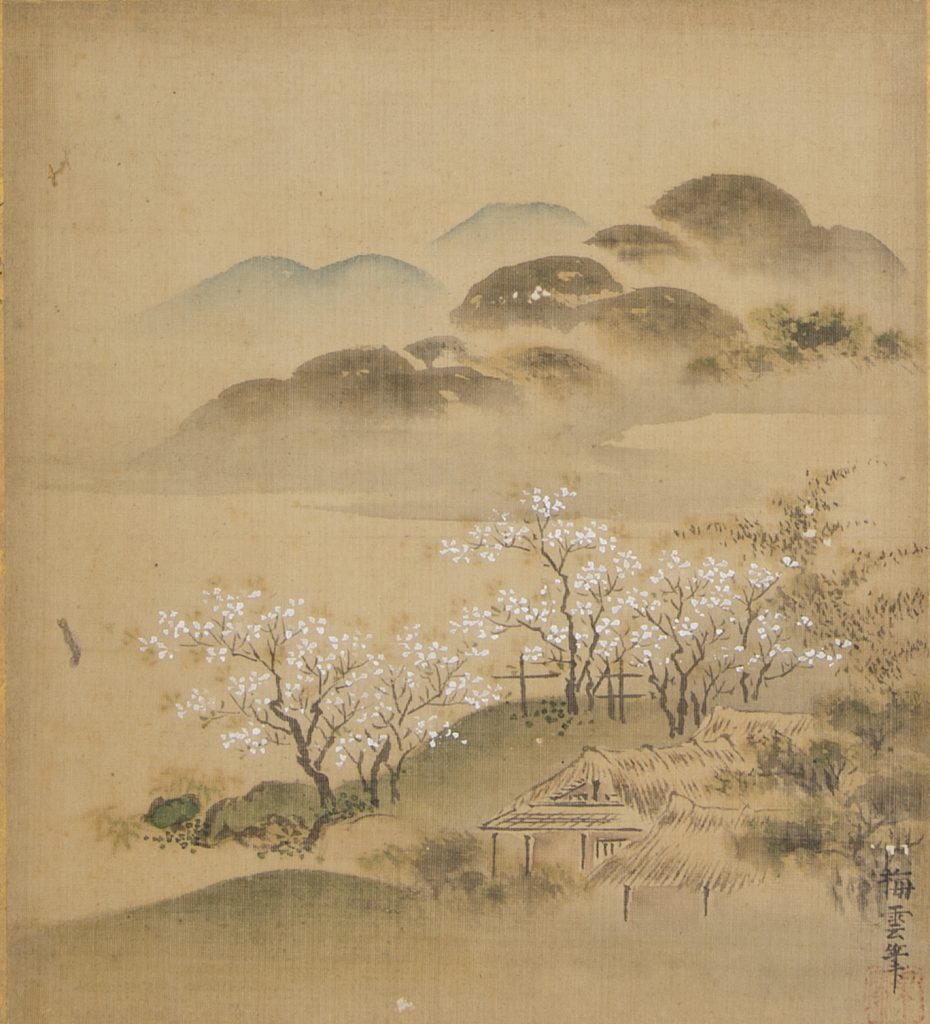

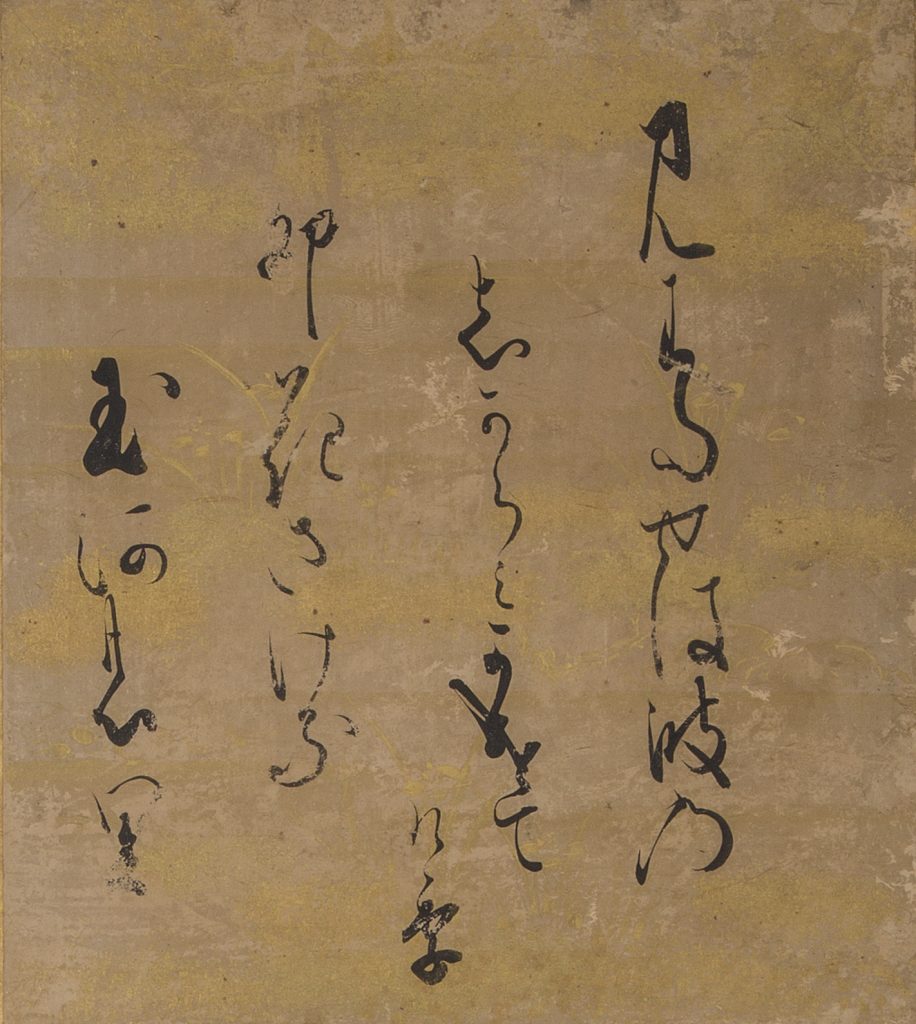

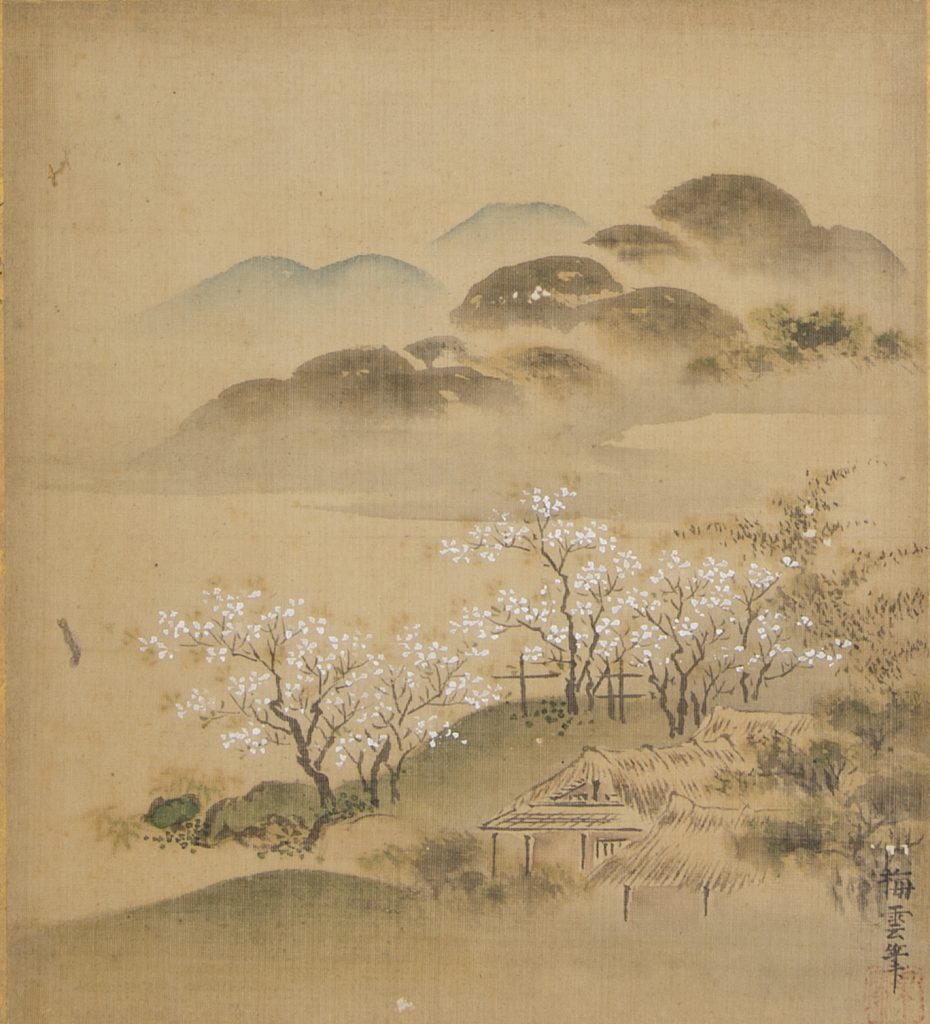

Panel 1, Noda no Tamagawa, The Jewel River at Noda

As evening gathers

salt winds blow from offshore

in Michinoku near

the sparkling Tamagawa of Noda

plovers now cry

Shinkokinshū. New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern, translated and introduced by Laurel Rasplica Rodd, Leiden: Brill, 2015

The poem was composed by Nōin Hōshi (988-1050) and appeared in the poetry collection Shin Kokin Wakashū (New Collection of Poems from Then and Now) from around 1205. The Jewel River referred to in this poem is Tamagawa at Noda in the province of Michinoku, also known as Mutsu Province. The place is known for its chidori, plovers, small waders with short beaks and a characteristic call. The painting depicts a landscape with white flowering bushes and a couple of thatched houses seen from a village by a lake or a wide river. Normally paintings illustrating this poem would depict the small chidori, plovers. It is therefore reasonable to think that this painting should have been placed next to the poem on panel 5, and was swapped around by mistake when the album was mounted on the screen. The white bushes in this painting look like unohana, deutzia, which are a place marker in the poem on panel 5. The painting on panel 5, which depicts a flock of plover, should presumably have been placed here.

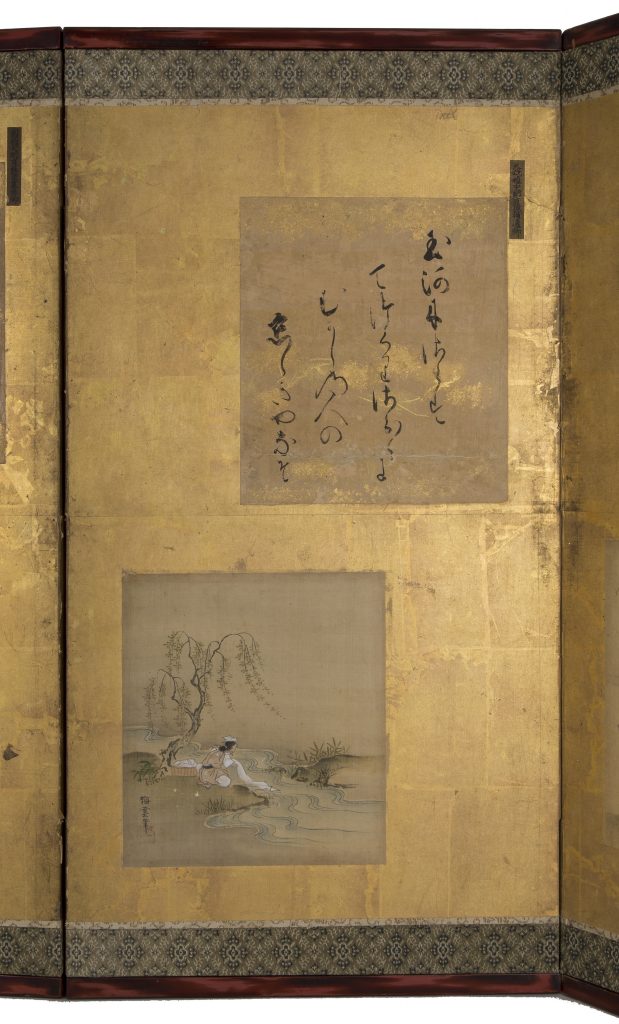

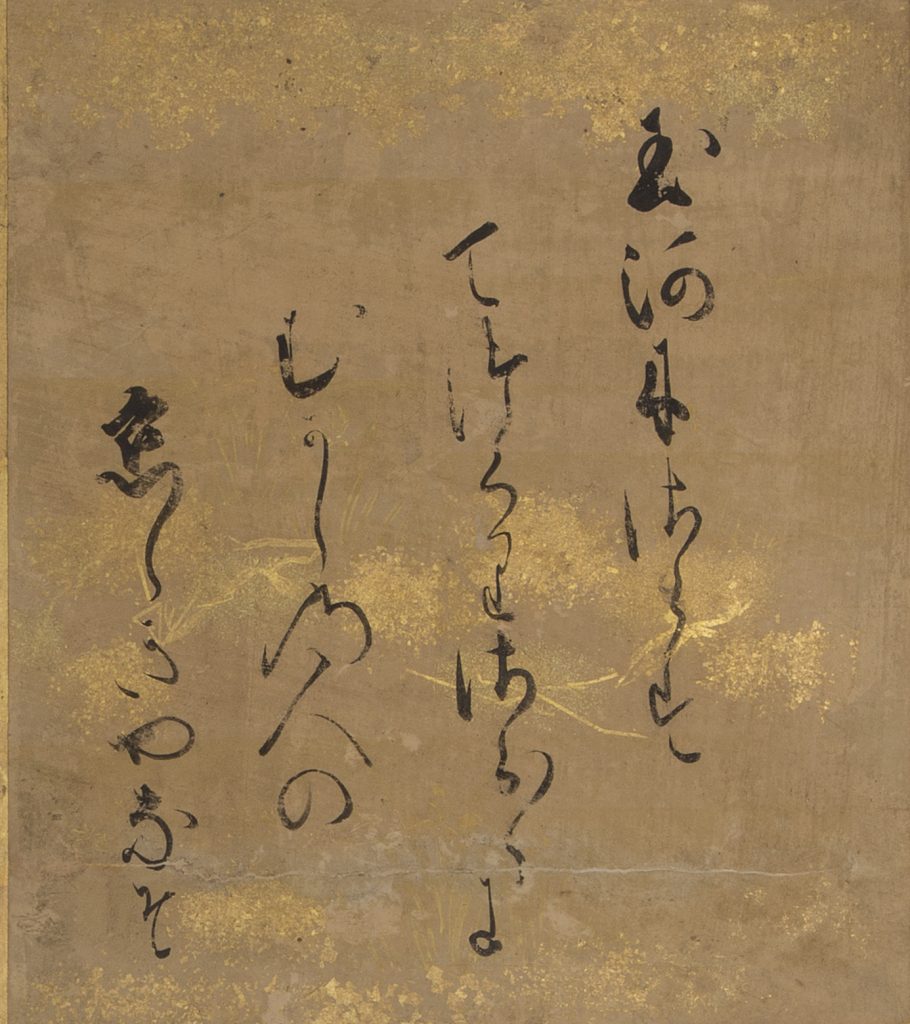

Panel 2, Tezukuri no Tamagawa, Bleaching Cloth at the Jewel River, or Chōfu no Tamagawa, The Jewel River at Chōfu.

By Tama River

homespun cloth hung out to bleach

rustling and trembling

how people in ancient times

believed so much in love

Translated by Gunhild Borggreen on basis of the Danish translation by Mette Holm and notes by Koji Yamada

The poem was written by Fujiwara Teika (1162-1241) in the poetry collection Shūi Gosōshū (Diverse Collections of Humble Herbs) from 1233. Even though there is no place name in the poem, it is linked to Chōfu, an area in the province of Musashi, which was known for the making of textiles. The painting shows a section of a landscape with a river. Under a willow tree a figure is seen kneeling at the river and rinsing white cloth in the flowing water. In this way the picture contains a visual reference to a word in the poem, tezukuri, meaning the hand-woven cloth that is rinsed in the river before it is hung up to bleach.

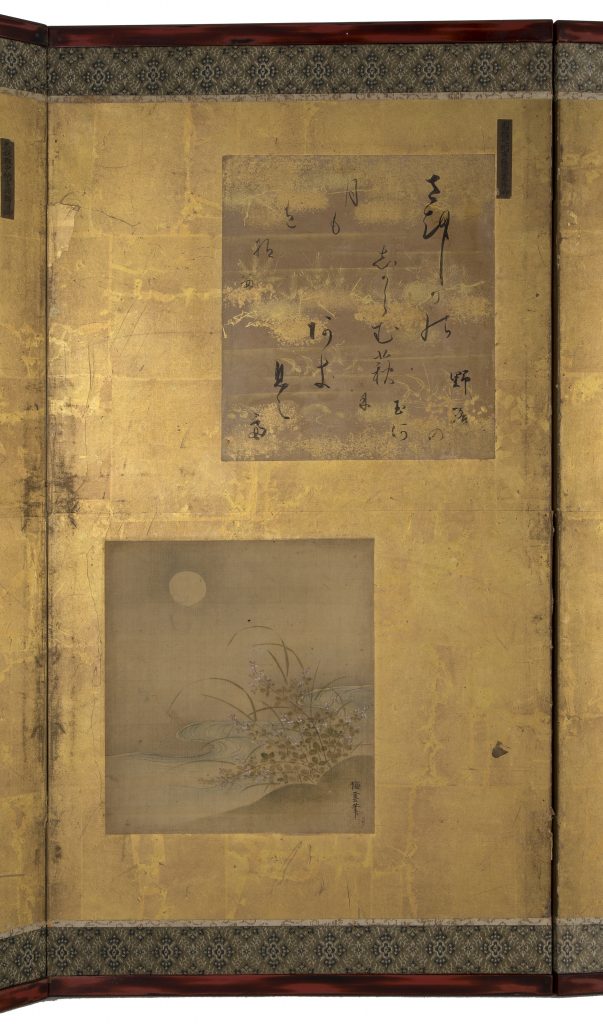

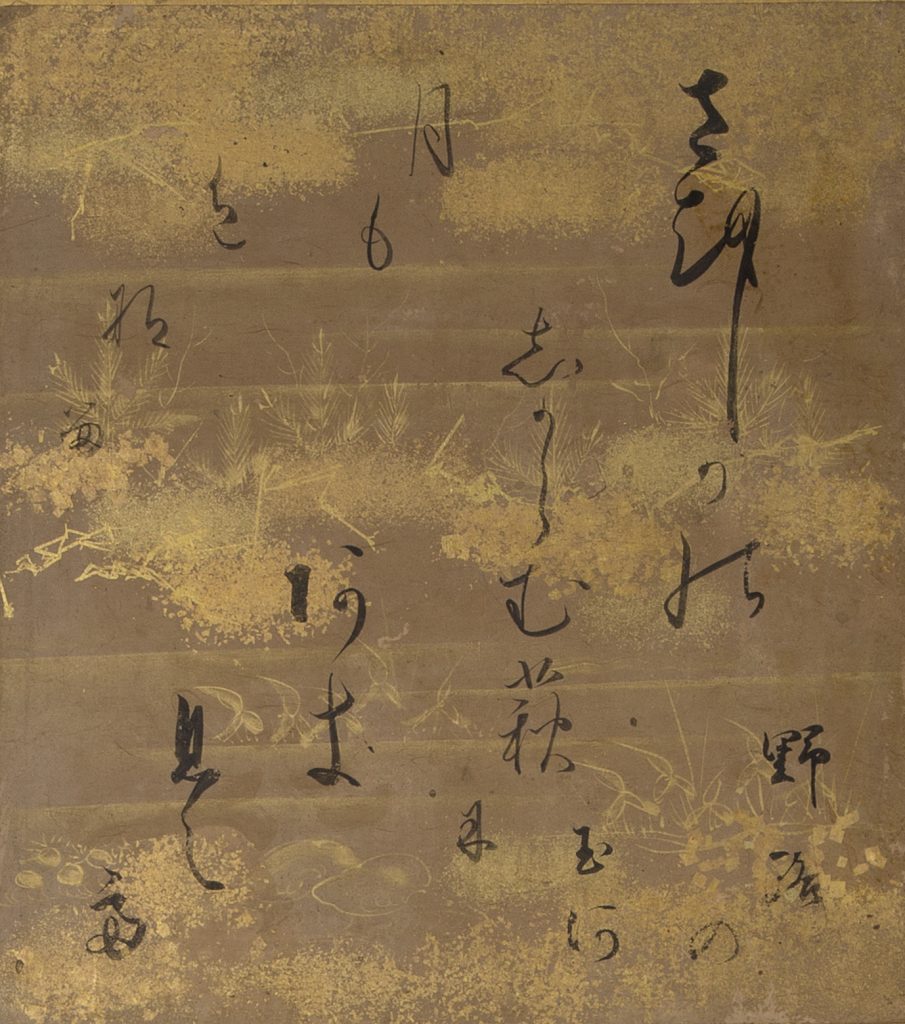

Panel 3, Noji no Tamagawa, The Jewel River at Noji

A deer entangled

in a branch of bush clover

he got bored by me

reflections of the moon on

Tama River af Noji

Translated by Gunhild Borggreen on basis of the Danish translation by Mette Holm and notes by Koji Yamada

The poem was composed by Fujiwara Nakamitsu (early 12th century) and included in the poetry collection Shinshūi Wakashū (New Collection of Gleanings) from 1364. Noji at Tamagawa refers to a place along the Jewel River east of Kyoto in Ōmi Province. Noji is known for hagi, a delicate bush with small, violet flowers and clover-like leaves. The bush clover blooms in the autumn, and is one of the seven autumn plants. The word tsuki (moon) is also a symbol that refers to the autumn. In the painting the artist has highlighted the luminous quality of the moon not by painting it, but by allowing the painting’s ground, the light silk, to shine through untouched by the brush. The landscape behind this small scene by the river is empty and creates an atmosphere of loneliness, which is also implied in the poem.

Panel 4, Ide no Tamagawa, the Jewel River at Ide.

I’ll stop my horse,

and give him water

on the shore of Tama’s stream

into which yellow roses drop their dew

The Shin Kokinshu. The 13th-Century Anthology Edited by Imperial Edict. Translated by H. H. Honda, Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press, 1970, p. 49

The poem was written by Fujiwara Shunzei (1114-1204) and published in the poetry collection Shin Kokin Wakashū (New Collection of Poems from Then and Now) from around 1205. The town of Ide lies to the south of Kyoto, in what was historically known as Yamashiro Province. Ide was already known in classical times for its yellow flower, yamabuki, kerria or pleniflora, as well as the imperial grazing areas for young horses. The artist has reproduced two main elements, horse and yamabuki, in the image. The horse with its rider is positioned in the centre of the picture, and it stands with its hooves in the water while it drinks. The rider’s dress shows that he is a person from the court or the aristocracy. The horse is also clothed in a fine harness with red fringes.

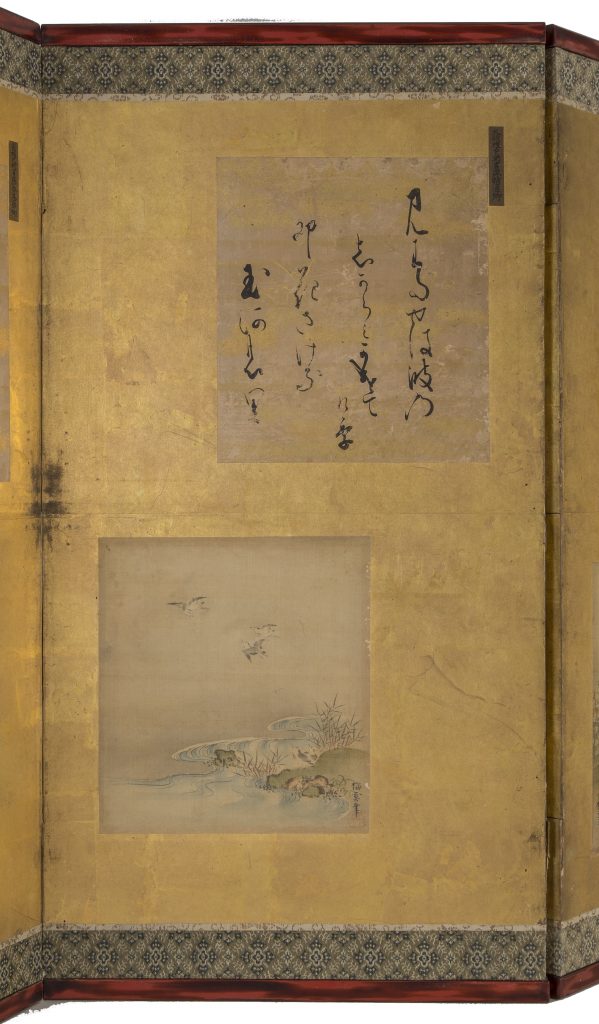

Panel 5, Unohana no Tamagawa (Deutzia at Tamagawa)

In my field of view

Waves are tumbling over waves:

To make this showing

Hareflower hedges in full bloom

At Tamagawa village!

A Waka Anthology. Volume One: The Gem-Glistening Cup. Translated, with Commentary and Notes, by Edwin A. Cranston, Stanford University Press, 1993, p. 457

The poem was written by the female poet Sagami in the 11th century and published in the poetry collection Shūi Gusōshū (Diverse Collections of Humble Herbs) from 1233. It refers to the province of Settsu, which today lies in the Osaka Prefecture. The place has been known since classical times for the unohana flower, the deutzia (hareflower), a hardy shrub with white, star-shaped flowers. In Baiun’s painting there are five birds, which look like the plovers referred to in the poem on panel 1. It is therefore likely that this painting was swapped around with the painting on panel 1, which depicts bushes with white flowers.

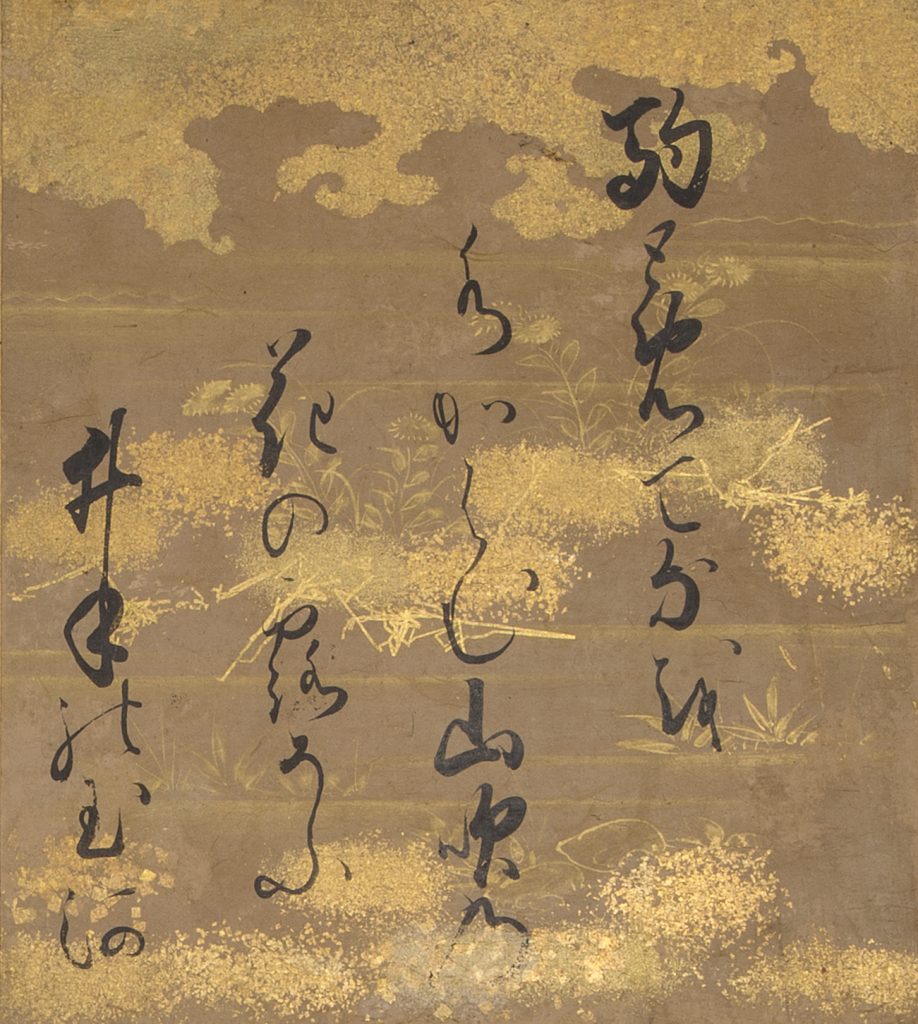

Panel 6, Kōya no Tamagawa, the Jewel River at Kōya

Forgetting the warning

not to do so

a traveler at the Tamagawa in Kōya

dips his hand in the water

The Mary Griggs Burke Collection, ”Shokoku Mu Tamagawa / Six Tamagawa Rivers from Different Regions”, at https://burkecollection.org/catalogue/494-shokoku-mu-tamagawa-six-tamagawa-rivers-from-different-regions

The poem was composed by Kōbō Daishi (774-835) and is part of the anthology of poems Fūga Wakashū (Collection of Elegant Poems), published between 1344 and 1346. Kōbō Daishi is another name for the monk Kūkai, who in 819 founded a temple in a valley of Mount Kōya south of Osaka, in what was historically known as the Kii Province. Mount Kōya is a well-known place of pilgrimage, and the poem refers to the inner area of the temple complex, where the local Jewel River has its source. Many pilgrims came here in order to pray at Kōbō Daishi’s grave, and drank the cool water of the Jewel River. But it is said that the water was poisonous, and that a sign was erected to warn travellers. It is this danger which is hinted at in the poem.

As mentioned two of the paintings on the Royal Family’s folding screen may have been swapped around, when sheets from an album were mounted on the screen. This can have happened because the combination of poems that represent the renowned places linked to Japan’s six Jewel Rivers has changed over time. This has influenced the iconography in a way that has led to the interchanging of two of the paintings on the Royal Family’s folding screen. Poems and paintings of the white flowers of the deutzia, unohana, disappear from the canon and are not found in later depictions of The Six Jewel Rivers. For this reason the Royal Family’s folding screen with poems and paintings about Mu Tamagawa, The Six Jewel Rivers, is quite unique and rare in the history of Japanese art.

Note

Published in July 2017.

© Gunhild Borggreen and Kongernes Samling / The Royal Danish Collection 2017.

A longer Danish version is available

here

Translation: Christopher Sand-Iversen.

Thanks to Joshua S. Mostow, Mette Holm, Koji Yamada, and Niels Lyngsøe for their help with the iconography and translations of the poems.

Dansk

Dansk

English

English

Deutsch

Deutsch